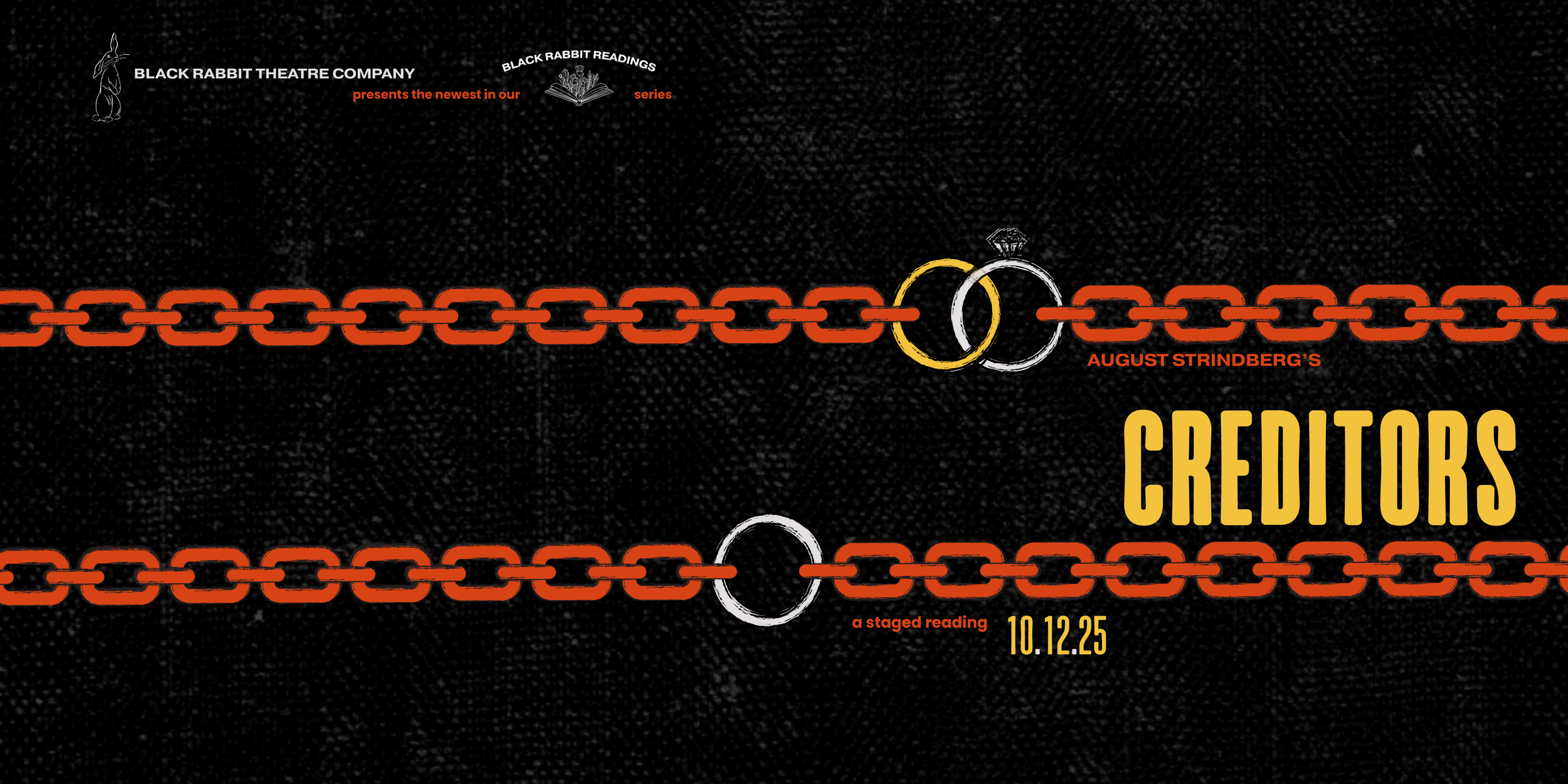

10.12.25

The Event

The debts of the heart are rarely forgiven, and every passion pays its price.

Tekla, captivating and self-assured, finds herself caught between two men: Adolph, her fragile young husband, and Gustav, the cunning ex-spouse who knows exactly how to exploit Adolph’s doubts.

What begins as intimate conversation twists into a high-stakes duel of influence, with Tekla at the center of a battle neither man intends to lose. As the tension mounts, old wounds reopen and hidden motives surge to the surface, exposing the toxic undercurrents beneath desire.

Strindberg crafts a razor-sharp portrait of psychological warfare, where the cost of love is measured in betrayal, manipulation, and emotional ruin.

Join us Sunday, October 12th at Thymele Arts!

Doors open at 6:30 for free snacks and wine

Reading starts promptly at 7:00

Tickets are pay-what-you-can ($5 minimum)

Students get in free with student ID

Free for Play of the Month Club members

(info at the link below)

GETTING THERE + PARKING:

Street parking is free on Sunday

There is an underground garage located at 1110 N. Western ($8 after 5 p.m.)

The Players

Matt McConkey

GUSTAV

Analisa Gutierrez

TEKLA

Sam Bixby

ADOLPH

The Play

A man. His wife. And her ex-husband.

August Strindberg’s Creditors (1888) is a taut psychological drama that distills the playwright’s fascination with human relationships, power struggles, and the unseen debts people owe each other. Set in a seaside resort, what begins as a seemingly intimate conversation spirals into a battle of wit and willpower, with each character pressing the others for repayment of emotional, intellectual, and spiritual “credit”.

With its compact structure and escalating intensity, Creditors has been celebrated as one of Strindberg’s most incisive works. Its sharp dissection of marriage and gender roles reflected—and scandalized—its late-19th-century audiences. Strindberg, himself embroiled in turbulent relationships and often accused of misogyny, drew on his own life to craft characters who embody the contradictions of intimacy: dependence and dominance, love and resentment, creation and destruction. In doing so, he tapped into broader societal anxieties about the shifting dynamics between men and women at a time when traditional structures of authority were under pressure. This raw honesty, unsoftened by sentiment, made Creditors both controversial and compelling, positioning it as a mirror of modern anxieties about relationships long before such themes became common on stage.

Over time, Creditors has earned recognition as a landmark of naturalist theatre and a precursor to the psychological realism later developed by playwrights such as Ibsen and O’Neill. Its relentless focus on emotional truth, its stripped-down setting, and its exploration of power through language anticipate much of 20th-century drama.

While the play has at times been overshadowed by Strindberg’s other works, it has steadily grown in reputation and is now considered one of his finest achievements—a piece that continues to provoke, unsettle, and resonate with contemporary audiences who recognize in its struggles the enduring complexities of love, debt, and human connection.

The Playwright

August Strindberg (1849–1912) was as infamous as he was influential—a volatile artist whose personal notoriety bled directly into his work. He was a novelist, painter, and essayist, but it was the theatre where he burned brightest. His plays strip human relationships down to their bones, exposing the cruelties and hungers that polite society preferred to ignore. Yet the very insight that makes his art so penetrating was fueled by a life of turmoil: paranoia, failed marriages, bitter feuds, and a restless disdain for compromise.

Strindberg’s reputation was as stormy as his work. He was accused — with reason — of misogyny, and his plays frequently cast women as destructive or manipulative forces, reflections of his own embattled experiences with love and marriage. He quarreled viciously with peers, famously sparring with Henrik Ibsen, and turned even friends into enemies. His fascination with the occult and descent into periods of near madness earned him both notoriety and pity. To some in the audience, he was a truth-teller willing to strip away illusions; to many in real life, he was a dangerous misanthrope whose art mirrored his own bitterness.

It is precisely this turbulence that secured Strindberg’s place in theatrical history. His naturalist works, like Creditors and Miss Julie, broke ground in their unflinching drama, while his later dream plays anticipated expressionism and modernist experimentation. He left behind a legacy as one of theatre’s great provocateurs: an artist whose brilliance, for better or worse, cannot be separated from his brutality. To encounter Strindberg is to face both his insight and his ugliness, a reminder that the most unsettling art often springs from the most unsettled lives.

Photo by Robert Roesler